【Deep Dive Chronicle】Mt. Hayachine: Serpentine Peak and Autumn Sky

Mid-October. The morning dawned clear, as if the previous day’s rain had been a lie. I headed toward Mt. Hayachine, the highest peak of the Kitakami Mountains at 1,917 meters elevation. Listed among Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains and 100 Flower Mountains, this serpentine peak—home to the endemic Hayachine Usuyukiso—was shrouded in clouds on the ascent, then revealed a sea of clouds beneath autumn skies on descent. These two contrasting days of climbing, following rain-soaked trails one day and blue skies the next, tell a story of the mountain’s many faces.

目次

Part 1: Early Morning from Genbu Onsen

Morning came early at Lodge Tachibana in Genbu Onsen. The previous evening, I had arranged with the lodge owner to have breakfast prepared as packed meals. My six clients and I departed while darkness still cloaked the valley.

Fatigue from the previous day’s rain-drenched climb on Mt. Mitsuishi remained in our bodies. Yet this morning’s sky had transformed dramatically from yesterday’s gloom. As I drove, relief washed over me at the weather’s recovery.

We arrived at the Odagoe trailhead shortly after 8:00 AM and began walking the forest road from Kawarano-bō toward Odagoe. My clients’ steps carried slightly more weight than yesterday—this was our second consecutive day in the mountains. I couldn’t push them too hard.

Mt. Hayachine—standing at 1,917 meters, it is the highest peak of the Kitakami Mountains and numbered among Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains and 100 Flower Mountains. The entire mountain consists of ultrabasic serpentine rock, making it a treasure trove of endemic species including Hayachine Usuyukiso (Leontopodium hayachinense). Since ancient times it has been revered as a sacred mountain, with Hayachine Kagura (a traditional Shinto ritual dance) still performed in the villages below.

This was just after the Liberal Democratic Party leadership election had concluded. In the Diet, debate over the Prime Minister designation continued. But the mountains remain untouched by such political clamor.

“The weather looks promising today,” someone said.

I nodded in agreement. After yesterday’s rain, today’s clear skies felt especially precious.

As we emerged from the forest and approached Mikadoguchi, clouds began rising around us. White mist closed in, obscuring our view. Perhaps remnants of yesterday’s rain? Or the mountain’s whim?

Around this point, one of my clients reported feeling unwell. The previous day’s exhaustion lingered, no doubt. It was around 10:00 AM.

“I’ll turn back here,” he said.

Pushing on would be unwise. As a guide, my judgment must always prioritize safety. I arranged for him to wait at the trailhead.

The remaining five clients and I continued our ascent.

Part 2: Ascending the Serpentine Peak

Beyond Mikadoguchi, the trail gradually became rockier. Mt. Hayachine is entirely composed of ultrabasic peridotite and serpentine rock. The characteristic gray-green stone spread beneath our feet.

Serpentine rock is notoriously slippery. Even with rubber-soled boots, wet sections demanded careful attention. Walking at the front, I called back continuously to those following.

“Slippery here. Watch your footing.”

My clients climbed steadily onward. Perhaps yesterday’s rain-soaked mountains had hardened them—no one complained.

Elevation markers appeared one after another. Third station, fourth station, fifth station. As we gained altitude, the trees grew sparse.

Past the fifth station, ladders appeared—steel rungs mounted against serpentine rock walls. I checked each one: wet or dry? Stable or shaky? Ascending carefully.

“One person at a time on the ladders. Take it slow.”

I looked back as I called to those behind. My clients climbed the ladders in silence. Yesterday’s rain seemed to have steeled them—no one voiced anxiety.

Then we encountered unexpected blooms.

One flower each of Nanbu-toranoo (Bistorta hayachinensis) and Miyama-kinbai (Potentilla matsumurae) remained tucked between rocks. This was mid-October. How fortunate they had persisted. The white flower heads of Hayachine Usuyukiso had already withered to brown. The flowering season had long passed.

We passed the seventh station and reached Tengu no Suberidaishi—”Tengu’s Sliding Rock.” True to its name, smooth slabs of stone tilted steeply upward. The fog remained thick. Views were minimal.

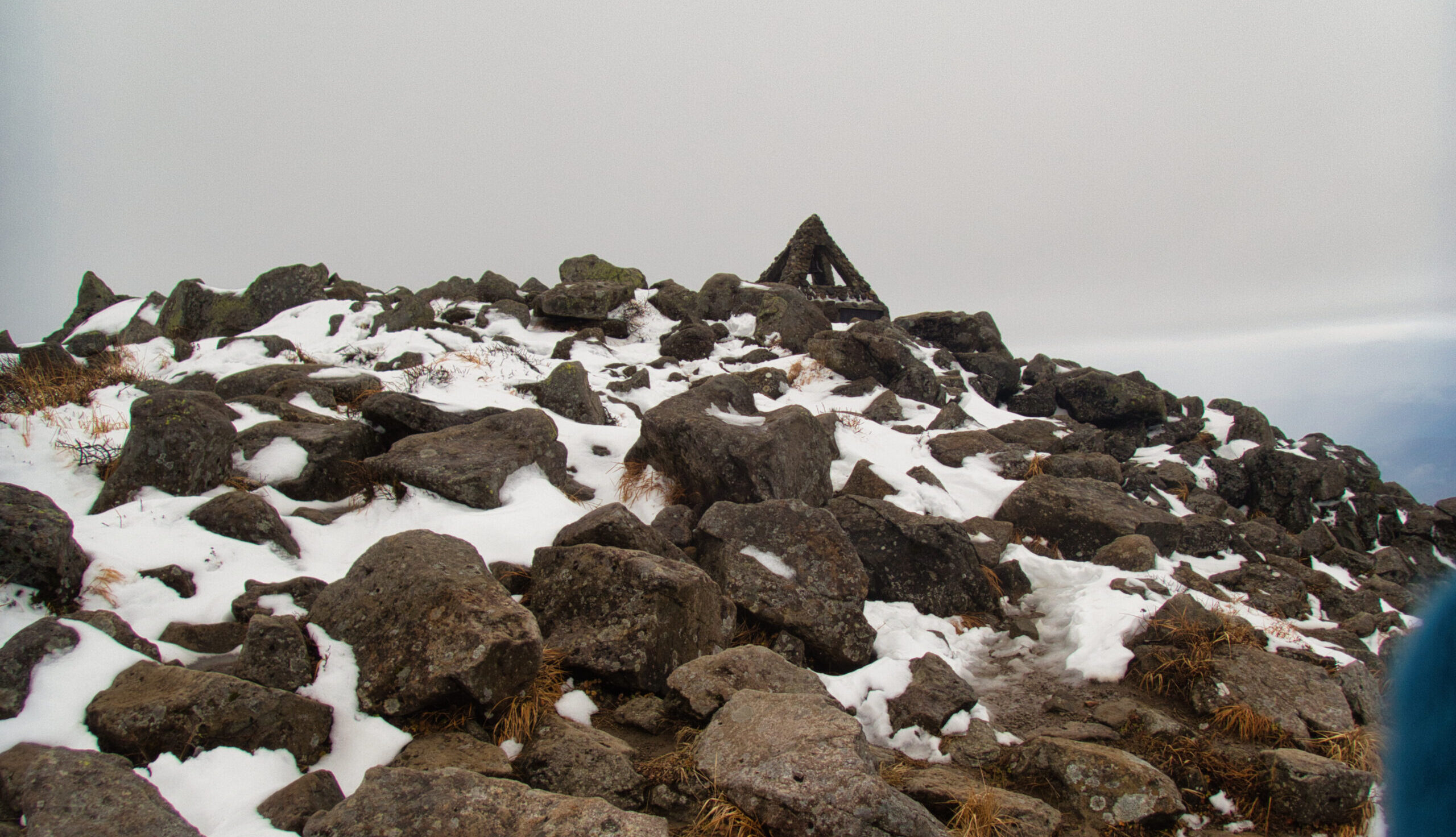

Still, the ascent proceeded smoothly. Past the eighth station and the fork to Kenganmine, we reached Hayachine’s summit just after noon.

Part 3: Return Under Autumn Skies

The summit was surprisingly warm—a stark contrast to the previous day’s exposed ridgeline on Mt. Mitsuishi. Though wrapped in clouds, the wind remained gentle.

I paid respects at the inner shrine of Hayachine Shrine. This is a mountain of faith. Since antiquity, ascetic practitioners have climbed here, and below, Hayachine Kagura has been danced. The weight of that history resides in these peaks.

After a forty-minute rest on the summit, we began our descent. Around the fork toward the Monma Course, the fog began to lift.

And there, spreading below us, lay a sea of clouds.

A white ocean stretched endlessly. In the distance, Mt. Iwate’s peak emerged above the blanket. After yesterday’s rain, the vista beneath clear autumn skies seemed almost unreal.

“Incredible,” one client breathed.

Everyone stopped to gaze at the sea of clouds. The transformation from yesterday’s rain to today’s glory seemed to erase our fatigue.

We descended the serpentine rock carefully. Downclimbing proved more treacherous than the ascent. I kept turning back, monitoring everyone’s progress.

Past Tengu’s Sliding Rock, down through the seventh station, the sixth station—steadily losing elevation. Below, autumn colors painted the mountainsides. Red, yellow, orange. Like flames consuming the slopes, brilliant hues blazed beneath the blue sky.

Entering the forest, the clouds cleared completely. Autumn sky peeked through the branches.

We descended to Mikadoguchi and entered the forest road toward Odagoe. From here, we were essentially safe.

Just before 4:00 PM, we returned to the parking area via Kawarano-bō. The mountain day had lasted roughly eight hours.

Yesterday’s rain on Mt. Mitsuishi. Today’s clear skies on Mt. Hayachine. Two contrasting days, yet both revealed essential truths about mountains.

Rain is also mountain. Clear skies are also mountain. And accepting all of it—that is what it means to walk in the mountains.

The flowers that bloom on this serpentine peak had finished their season. Yet one blossom each of Nanbu-toranoo and Miyama-kinbai added color to October’s mountain. That alone made this climb worthwhile.

LOG SUMMARY

- Date: October 13, 2025 (Monday) [Day hike]

- Team: 7 members (1 guide, 6 clients)

- Mountain Area: Mt. Hayachine (Hanamaki, Tono, and Miyako Cities, Iwate Prefecture)

- Route: Kawarano-bō → Odagoe → Mikadoguchi → Third Station → Tengu’s Sliding Rock → Mt. Hayachine Summit → Return via ascent route

- Duration: 7 hours 53 minutes (including breaks)

- Grade: Class 2 (Yosemite Decimal System) – Moderate trail with ladder sections and slippery serpentine rock. 900m elevation gain, approximately 8 hours round trip

- Accommodation: Day hike (Previous night: Lodge Tachibana at Genbu Onsen)

- Weather: Clear (Ascent: fog/clouds; Descent: clear with sea of clouds)

- Starting Point: Genbu Onsen (early morning departure) → Trailhead (arrived approximately 8:00 AM)

- Notable Features: Second consecutive day after Mt. Mitsuishi climb, warm summit conditions, sea of clouds visible on descent, one bloom each of Nanbu-toranoo and Miyama-kinbai observed, Hayachine Usuyukiso showing only dried flower heads